To the rest of world, sake is an alcoholic drink imbibed by many in the Far East, mostly in the company of good friends with food. It was discovered originally by the Chinese and introduced to Japan about 700 years later, where in the 3rd Century, Kuchikami Sake was first recorded. This mouth chewing sake consisted of rice, millet, chestnuts and acorns chewed by young maidens and spat into bowls and left to ferment. Sake certainly has evolved and refined immensely by the Japanese since.

As a drink, sake is less acidic, more alcoholic, certainly cleaner and, in a lot of cases, sweeter than wine and beer. A complicated little tipple with complex fermentation, this wonderful drink is found mainly standing proudly in “expensive” premium shops lovingly hugged in its handsome vertical vessel waiting eagerly to be sold to some connoisseur to enjoy. Little pretension and is certainly not a “faddy” item. A sort of ‘Marmite Moment’ – you either love it or hate it.

To my knowledge NO one makes non alcoholic Sake. Sake is very localised with very different characteristic taste profiles in the different regions of Japan. This is probably determined also by the different local ingredients and food preference. Most sake produced is drunk locally with only 3% of production exported. Although there are specific large sake producing areas, most Prefectures have breweries. The top 5 giant sake producers account for 49.5% of total sales. Due to it’s rising popularity, sake is now brewed outside Japan with USA leading the league table. Even Norway and the UK are now producing sakes. Sake microbreweries are popping up around the world. Home brewing of sake is definitely possible and can be very successful. Sake making kits are available.

Sake, Nihonshu or Seishu, translated as “Japanese Alcoholic Beverage”, is made from rice, water, komekoji (koji) and yeast, with some lactic acid to keep the yeast under control during fermentation. In the later stages, a little diluted distilled alcohol can be added for improvement of flavour. Unlike wine or beer, sake has UMAMI, over and above the sweet, sour, salty, bitter and chili/spicy taste profiles, logged by the tongue, nose and brain. Aromatically, sake is more complex with tropical fruit like esters of pineapples, melon and bananas being OK on the nose and taste profile. These constitute the fruity profile of sake known as “Ginjo-ka”. A third dimension of taste constitutes the creamy, cheesy sometimes blue cheesy nose due to the lactic acid used in sake production. These lead to a more savoury, funky-er, drier style of sake. Mostly found in sakes of the Yamahai/Kimoto method where lactic acid is produced from scratch (where a culture of lactobacilli is added to the mash and cultured) in the sake making procedure. You never find a “corked” sake as corks are not used but then again you never lay sake down with the liquid in constant contact with its screw top or plastic cork-like closure. Rust can be a potential hazard but rarely happens as the sake is drunk fairly quickly!

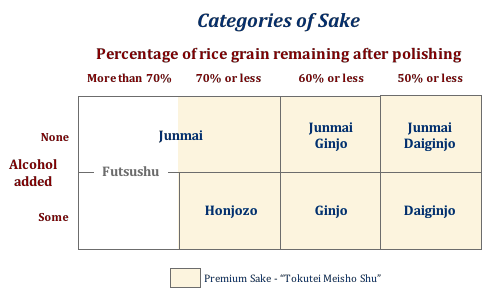

Sake is divided into two categories, namely non-premium (fusutshu) making up about 70% of the total sake production and premium sake (tokutei meisho shu). The classification of premuim sake (set up in the 1970’s) is based on % polish of grains of rice used in the brewing and whether distilled alcohol is added after fermentation.

A further term “tokubetsu” is sometimes used and this just means “special” and relates to an added brewing step or deviation from standard brewing procedure, making the sake special.

Sake can be drunk hot, warm, room temperature, cold and sometimes with ice. A beautiful Japanese poem of how to drink sake suggests 10 different temperatures to drink this ancient elixir based on the seasons of Japan and where/what a Japanese person would be doing while imbibing this gorgeous drink. Sake can be crystal clear, cloudy, murky, sparkling or a conbination of all the above. Most sakes are diluted before bottling but again, undiluted sake exists with no more than 22% total alcohol in volume. A further category of “pasteurisation” is thrown into the mix where sake can be pasteurised before, after or both at the bottling process giving very interesting results. Unpasteurised sake is drunk fresh and should be treated almost like drinking milk. Sold as soon as it’s made and drunk fairly quickly else fermentation continues (indefinitely) and changes the profile of the sake constantly! Namazakes and Nigori-sakes are always stored in the dark at <5ºc and once opened, drink up! Generally, most sakes are drunk fresh or fairly fresh and certainly within a year of its bottling though there are exceptions with the delicious aged KOSHU sake, some kept for tens of years in bottles, barrels and vats.

First produced in the Shinto shrines of Japan, sake was a key element in many religious rituals. Traditionally, a celebratory drink sipped at births, weddings and special occasions. It expresses the beauty, nature and spirit of Japanese culture and seasons. Sake is now drunk more regularly.

Serving sake can be tricky but rule of thumb – you get to pick the preferred vessel of your choice. Drink with friends who care for you. It is rude to pour your own sake. In true Japanese culture, the smaller the choko (cup) the more polite and civilised you and your friends are. You pour eachother sake throughout the evening serving eachother regularly and often, enjoying eachother’s company!

The making of sake involves a number of stages with larger breweries using machanised systems. Small artisan breweries still believe in handmade sakes. Sake can only be made from October onwards through to the end of March with the best sakes brewed in the colder months towards the end of the sake brweing season.

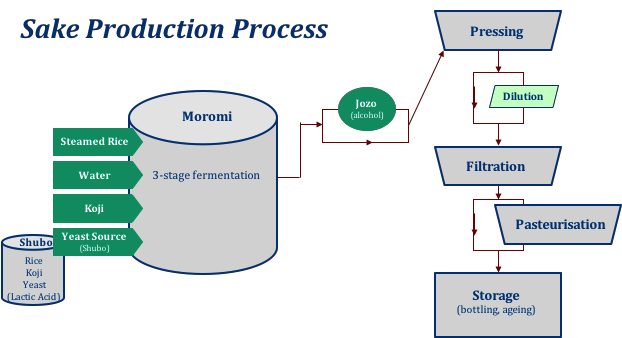

Sake is in true Japanese terms WASHOKU. All stages of its manufacture is from its original base ingredients. SLOWFOOD all the way with no short cuts hence so special. Over the years, the number of sake breweries have declined tremendously. There are now less than 1250 (2013) breweries left in Japan and dropping rapidly. This attribution can be linked to aged labour as future generations are unwilling to take over the small businesses, living in rural communities, preferring to be in the high energy big cities. It made by multiparallel fermentation method, where steamed rice is broken down by the koji to create a sugar solution which inturn is turned into Alcohol by the yeast cells. For this to happen a very fragile equibibrium is maintained throughout the fermentation/ brewing timeframe.

Rice (starch) + Koji + water => Sugar

Sugar + Yeast + water => Sake (alcohol)

Both these reactions take place in the MOROMI and initially in the SHUBO

The life of sake begins with little rice grains, grown in carefully manicured fields, nurtured lovingly over the spring and summer months in Japan. Harvested in autumn, the rice is painstakenly threshed, dehusked and left to dry naturally. There are about 100 sake designated rice varieties (all non sticky) though some specialist/funky sakes have been made with table rice, sticky rice and speciality rice like red or black rice. Only 5% of rice grown in Japan is destined for sake making of which 60% is made up of Yamada-nishiki and Gohyaku-mangoku. There are five main varieties most chosen by sake breweries with Yamada-nishiki being the top and most expensive. Others being Gohyaku-mangoku, Miyama-nishiki, Dewa-sansan and Omachi, which is thought to be the oldest native variety. Omachi today, can be found in two-thirds of all sake rice crossbreeds.

Sake rice grains are generally larger (25–27g per 1000 grains of rice) than table rice grains and contain a lot more starch in its inner layers (the shinpaku). The grains are graded by a very sophisticated system based on size of grain, maturity of the rice grains and ratio of broken and cracked grains. This grading system determines the price of rice for sake making.

Sale of rice in Japan for sake making is controlled as with the yeasts and brewing in general. It is still illegal to brew sake at home, in Japan. This stems back to the world war years where money was needed for the war effort and alcohol and sake tax was high. Alcohol consumption played a big part in the hard times and with farmers and men drafted to fight, farms were left unattended. It was at this stage that distilled achohol imported from Brazil was allowed to be added to increase the percentage of alcohol.

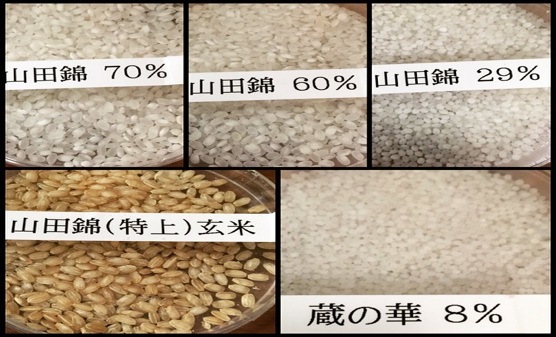

Once the variety and grade of rice is chosen, the making of sake can commence. The rice grains are first polished to remove the outer bran (nuka), vitamins, proteins, fats and minerals which are thought to spoil the flavour of sake. This is done by big mechanical highspeed rollers taking 5–6 hours to polish grains to 70% and up to two days to polish grains to 50%. The lowest percentage recoded to date is 8%, polished by a very special technic to keep the oviod shape of the rice grain. As a rough guide, one kilo of rice makes 1.8 to 2.5 l of sake.

The rice grains are washed and carefully soaked to the exact second before steaming. Water is very important in sake making and affects the final taste and aromatic profiles. Hard water with its minerals affect the yeast in the brew resulting in extra flavours and iron causes colouration the final sake.

Sake is made from rice that is totally COOKED (steamed rice). This steamed rice is used all three stages of the sake making process.

(1) The making of komekoji (Koji)

The BEST steamed rice with a soft centre and harder outer layers is innoculated with Kojikin or aspergillus spores to make Komekoji or koji infected rice grains – one of the main ingredients in Sake making.

Making Komekoji can take up to two full days in special contamination free rooms called kojimuro. The cooled rice is spread on clean cotton sheets and kojikin (aspergillus spores) is innoculated by hand using a sprinkling cannister. The rice is then wrapped up to allow the aspergillus to germinate and grow at 32ºc in relatively high humidity. Then painstakingly, the rice is unwrapped and declumped regularly for the next 10–12 hours making sure the temperature and humidity remains constant for optimum aspergillus growth on the rice grains. The cooked rice grains will be fully infected with aspergillus and this is now known as the komekoji (koji). The koji infected rice is then left dry in different sized boxes – Futa (1.5kg rice), Hako (15–40kg rice), Toko (100–300kg rice). This determines the eventual infection rate of the aspergillus. There are two styles of infection and depending on the particular style of sake required, the choice can be so-haze or tsuki-haze koji.

(2) SHUBO (mother of sake or starter sake) for the culture of starter yeast and lactic acid (and technically sake) as Komekoji is also added together with water to initiate the multiparallel fermentation.

Rice is needed in the shubo where starter yeast is cultured along side with lactic acid in a highly acidic environment. The shubo is probably the most important and complicated step of sake making. Acidity and temperature to control the culture of yeast and lactic acid creating a balanced environment for the production of sake.

Production of starter yeast is very much controlled by the Brewing Societry of Japan (1906) and later the National Research of Brewing (NRIB) formed in 1911. There are a number of yeasts that are specifically designated for sake brewing. The Kyokai-Kobo the brewing society starter yeasts are numbered from #6 to #15 and their non-foaming versions #6–01 to #18–01. (#6 – #12 are the same as the older #1 – #5) Each number representing a different style and aroma of sake produced. Sake yeasts are very different to wine and beer yeasts, and play a big part in determining the quality of sake produced. They can withstand low temperature (5–6ºc) and higher alcohol content (19–20%Alc). The current most used yeast for sake making is #7, a versatile fruity number!

Lactic acid can be added directly into the shubo (sukoju moto) for cheaper and faster brewing, else, for more expensive or traditional styles the MOTO (base) method is used. There are four main lactic acid producing methods and will be written on the sake label if used. In these cases, lactobacilli are cultured separately before adding into the shubo. Kimoto, Yamahai, Bodai-moto, KouonTouka. These base methods can take up to 4 weeks to make the lactic acid hence prolonging the brewing time for sake.

(3) MOROMI – the main brewing/fermentation tank. Once the shubo environment is steadily progressing in equilibrium, the main brewing can begin. The shubo together with more rice, koji and water are poured into the moromi. The main mash takes six days to prepare in three stages. Roughly, the ratio of sake ingredients are

80 rice : 20 koji : 130 water

After anything between 18 to 45 days of waiting, sake mash is now ready for the next production stage.

At this point, the Toji (sake master) decides whether extra enhancing ingredients like fruit (Yuzu), sake lees or Jozo (alcohol) made from molasses or grain is to be added.

Pressing of the mash is done by various methods. This stage is done to remove the impuriies, dead yeast cells and rice remains and forms the sake kasu, a ‘cake like’, creamy coloured mass. Sake kasu is very nutritious and is used for further fermention (shochu), pickling vegetables, eaten or used in animal feed. This procedure determines the style of sake. The mash can be pressed by various methods:

- Fukuro-shibori- gravity method – the mash is placed in cloth sacks and hung from wooden stakes. Sake drips freely into containers. Three different stages of sake is collected, namely the Arabashiri, Nakagumi/Nakadori and the Seme. This method tends to be only used for competition sake and a very time consuming method.

- Yabuta-shibori – by far the most efficient and used method. A large vertical accordion style set of bags are filled with mash and pressed by bubble like bags filled with air.

- Fune-shibori – the boat method where cloth bags of sake mash is place horizontally in a wooden boat-like frame and gentle pressure is applied from a top heavy weight.

- Enshin-shibori – Centrifugal separator, a very expensive piece of equipment but, fast.

The first pressing produces a cloudy liquid. If left to stand in cool temperature, it will precipitate leaving a clean clear liquid. At this stage, dilution can be done before filtration. The filtration is done using passing the pressed sake through either paper or charcoal. Unfiltered sake is known as muroka. The clear sake now has to be stabilised and micro particles such as remaining lactobacilli, yeast and koji enzymes to be rid off for this the fastest and best method is for pasteurisation at 60ºc to take place. Pasteurisation can be done by

- heat exchangers

- in the bottle

- in tanks

Namazakes are sakes that have not been pasteurised. These sakes are delicious and rarely available outside of Japan. They are mostly drunk as fresh as possible.

Sake breweries will produce a large number of sakes in a season and it will be impossible to buy any one sake throughout the season. Distributors biggest headache as some breweries will only offer what they have, sometimes as little as 100 bottles for the year. 56% of Japanese sake producers make less than 100 kilo litres of sake per annum.

Once bottled, a sake label always has

- its brand, name or brewery name

- date of bottling

- style of sake – non premuim or premium

- if premium, a detail description including any particular brewing methods including rate of polished grains, the final alcohol by volume, non pasteurised, non filtered and in many cases the rice used.

With this knowledge it is hoped that sake can be wisely chosen and enjoyed. With gracious thanks to GEN for the scholarship to Mie Prefecture.